Book: The Divide

Saturday 01 April 2017 I picked up The Divide: American Injustice in the Age of the Wealth Gap, by Matt Taibbi because I was looking for another book of his, Griftopia, but I couldn't find it in English here in Switzerland. The book was about how income inequality is tied to inequality in the American justice system - specifically how the poor are jailed in huge numbers for ridiculously silly things, while the rich can literally steal billions of dollars and only get a slap on the wrist.

I picked up The Divide: American Injustice in the Age of the Wealth Gap, by Matt Taibbi because I was looking for another book of his, Griftopia, but I couldn't find it in English here in Switzerland. The book was about how income inequality is tied to inequality in the American justice system - specifically how the poor are jailed in huge numbers for ridiculously silly things, while the rich can literally steal billions of dollars and only get a slap on the wrist.

This is a subject with which I am intimately familiar, so there wasn't really anything new to me in this book. However, Taibbi really points out just how unjust the justice system is with detailed examples of how different types of people are treated completely differently. At one end of the spectrum in welfare fraud, which is aggressively prosecuted by states, and often incorrectly prosecuted. The welfare system is a vast bureaucracy where people are often charged with fraud where none exists - and without money to hire lawyers the defendants have absolutely no chance to beat the cases. So a poor single mother can be charged with fraud for basically any or no reason, and if she can't pay the money the state asks of her she risks facing felony fraud charges and jail time.

An example on the other end of the spectrum is HSBC, a massive multinational bank which was accused of working with drug cartels and terrorists to launder billions of dollars. In a deal typical of these types of white collar crimes, HSBC paid a fine of $1.9 bn, and faced no criminal charges. The US government felt that HSBC was "too big to fail" and feared that filing criminal charges could crash the world banking system.

Personally, I don't think it makes sense for corporations to face criminal charges. Despite what the Supreme Court says, a corporation is not a person and can't make it's own decisions to engage in criminal behavior. An actual person had to make those decisions, and they should face the criminal charges. However no one at HSBC was charged with any crimes, nor were any of the banks whose actions led to the 2008 crisis charged with any crimes. The only bank charged with crimes related to the sub-prime mortgage crisis was a small bank in Chinatown, NY - which had no issues with subprime mortgages and thus no relation to the crisis, but which was scapegoated so that the government could say that they had prosecuted at least one bank.

American schools teach the propaganda that the US is a class-less society, where by hard-work and grit anyone can become rich. While this is a completely false statement - the US ranks near the bottom of developed countries as far as social mobility, it is perhaps considered a little white lie, encouraging people to work hard. The damage comes from the fact that this belief implies that if someone is not wealthy it is because they are lazy or unintelligent. So anyone who needs any kind of financial assistance is a priori assumed to be deficient in some manner. On the other hand someone who has money is considered to be superior, regardless of the facts or circumstances which led to them having the money. While there are some notable examples, such as Bernie Madoff, there are numerous other cases of wealthy hedge fund managers basically raping and pillaging the lower classes for a few extra bucks who are never even charged with a crime.

According to John Erlichman, who was an advisor to President Nixon, Nixon's motivation for launching the "war on drugs" was to politically target two groups of people who he disliked - the blacks and the anti-war movement. He couldn't overtly target those groups, so he instead decided to criminalize and focus on two drugs he felt were associated with those groups - heroin and marijuana, respectively. This has led directly to the huge incarceration rates in the US. The fact that different types of crimes are treated so differently is basically a continuation of this policy, except now anyone who is not a corporation and not fantastically wealthy is being targeted, with the crimes associated with poorer people being treated far more harshly than others. In this case, it is not a personal vendetta that is driving the laws, but the vast political influence the wealthy and corporations have over the government.

Labels:

books,

politics

No comments

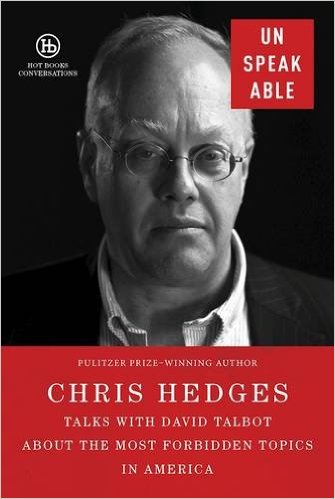

Chris Hedges is someone I respect a hell of a lot. He is one of the few people today who is not afraid of really just speaking the truth. Despite all of Trump's talk about how the media is all fake news, the mainstream media in fact really just toes the party line as far as corporate interests. The sad truth in American politics today is that once you get past all the little details that the two political parties try to get people all worked up about the two parties really agree on most economic issues. The two parties get their constituents all riled up about issues that honestly won't really effect people's lives that much - and while everyone is busy arguing over who can urinate in what bathroom they conduct the real work of the government which essentially is catering to large corporations.

Chris Hedges is someone I respect a hell of a lot. He is one of the few people today who is not afraid of really just speaking the truth. Despite all of Trump's talk about how the media is all fake news, the mainstream media in fact really just toes the party line as far as corporate interests. The sad truth in American politics today is that once you get past all the little details that the two political parties try to get people all worked up about the two parties really agree on most economic issues. The two parties get their constituents all riled up about issues that honestly won't really effect people's lives that much - and while everyone is busy arguing over who can urinate in what bathroom they conduct the real work of the government which essentially is catering to large corporations. The Reactionary Mind: Conservatism from Edmund Burke to Sarah Palin, by Corey Robin, is a book of essays about conservatism from the 17th century to today. I have often struggled to try to figure out exactly what "conservatism" as a political philosophy actually means and I thought this book might shed some light. While it did have some interesting ideas, it didn't really do that great of a job answering my question.

The Reactionary Mind: Conservatism from Edmund Burke to Sarah Palin, by Corey Robin, is a book of essays about conservatism from the 17th century to today. I have often struggled to try to figure out exactly what "conservatism" as a political philosophy actually means and I thought this book might shed some light. While it did have some interesting ideas, it didn't really do that great of a job answering my question. When I first heard of this book I assumed it was an anti-Trump gimmick, designed and written solely to sell copies by capitalizing on the anger at Trump's election. It wasn't until I discovered that the book was written by Matt Taibbi that I actually decided to read it. Matt Taibbi is the author of what I consider to be one of the most important books on politics in this century "The Great Derangement," which analyzes recent fringe conspiracy movements in the light of what US politics have become. In "The Great Derangement" Taibbi investigates one right-wing movement - apocalyptic religious fundamentalists - and one left-wing movement - 9/11 Truthers - and concludes that both stem from the fact that the American political system has become so corrupt and so removed from any real democratic influence. Rather than getting angry that the government acts mostly in the interest of the multinational corporations and monied interests who fund the politicians and agitating for any real change, people instead focus on fringe conspiracy theories and become obsessed with the coming of the rapture or trying to figure out who was "really" behind 9/11. In the meantime the political parties promote the idea that they are idealogical opposites by getting the people to focus on and get angry about social issues like what bathrooms transgender people can use, gay marriage and abortion while both parties take jam through their agenda which benefits the very wealthy and the multinationals. But enough about that book...

When I first heard of this book I assumed it was an anti-Trump gimmick, designed and written solely to sell copies by capitalizing on the anger at Trump's election. It wasn't until I discovered that the book was written by Matt Taibbi that I actually decided to read it. Matt Taibbi is the author of what I consider to be one of the most important books on politics in this century "The Great Derangement," which analyzes recent fringe conspiracy movements in the light of what US politics have become. In "The Great Derangement" Taibbi investigates one right-wing movement - apocalyptic religious fundamentalists - and one left-wing movement - 9/11 Truthers - and concludes that both stem from the fact that the American political system has become so corrupt and so removed from any real democratic influence. Rather than getting angry that the government acts mostly in the interest of the multinational corporations and monied interests who fund the politicians and agitating for any real change, people instead focus on fringe conspiracy theories and become obsessed with the coming of the rapture or trying to figure out who was "really" behind 9/11. In the meantime the political parties promote the idea that they are idealogical opposites by getting the people to focus on and get angry about social issues like what bathrooms transgender people can use, gay marriage and abortion while both parties take jam through their agenda which benefits the very wealthy and the multinationals. But enough about that book...