Book: Einstein's Intuiton by Thad Roberts

Tuesday 27 June 2017 Einstein's Intuition, by Thad Roberts. is one of the most amazing books I have read in a long time. I saw Thad giving a TED talk about visualizing nature in more than the four dimensions we normally experience, and then before it was even over I started trying to track down this book.

Einstein's Intuition, by Thad Roberts. is one of the most amazing books I have read in a long time. I saw Thad giving a TED talk about visualizing nature in more than the four dimensions we normally experience, and then before it was even over I started trying to track down this book.

I have always assumed that there are more dimensions than the three spatial and one time dimension we humans are familiar with. The biggest objection to this assumption is usually: "if they exist, why don't we see them?" As far as I'm concerned the answer is because perceiving them doesn't contribute to our survival, therefore there is no evolutionary advantage to perceiving them. More typical answers from the scientific community are along the lines of "they are very small" or "they are rolled up."

When I read "A Brief History of Time" as a child, I became fascinated with cosmology and quantum mechanics. One of the key ideas of quantum mechanics is that we can't know where a particle is or where it is going. To represent them quantum mechanics uses a "wave function" which is essentially a probability wave that gives you the probability that the particle will be in a certain location at a certain time. As a child I thought this was unbelievably cool, but as I grew and I thought more about it I started to have trouble with the interpretation of this concept. The typical interpretation of quantum mechanics is that the particle is not actually in any one location until we measure it, at which point the wave function collapses and the particle solidifies to a specific location. This has two rather disturbing implications. The first is that we humans somehow control the universe by the act of observing it, (this idea is explored in the fantastic fiction book by Greg Egan "Quarantine.") In my opinion this idea is the height of hubris, giving humans near magical powers to change the universe with our minds. The second implication is that the universe is stochastic, meaning that it is essentially random - we can predict probabilities but it is impossible to predict anything for certain.

Over the years I had convinced myself that the wave function was in fact a probability wave, and that we humans just couldn't know for sure where particles are going to be because of the limits of our minds and our technology. I thought it was crazy for scientists to actually think that the universe is random, that "god plays dice with the universe" to paraphrase Einstein. In my mind, that thought contradicts the whole basis of science. I believe that if one had complete knowledge of the universe, of every single particle's position and energy at any given point in time, one would be able to know exactly where every particle would be at any point in the future. The problem with this is that to model the entire universe one would need a computer that is far bigger than the entire universe, the easiest way to model the universe would be with an exact copy of the universe, which is obviously rather impractical.

The part of Thad's TED talk that grabbed me in was when he showed a simulation of what it would be like to be a two-dimensional being. He showed a line that had colors of different sizes flashing on it in different areas for different amounts of time. There was no discernible pattern. Then he widened the perspective by a dimension, showing that the line was in fact a line cut from a video of a pool table with balls bouncing around it. When we add the extra dimension in it is easy to find the patterns, from the two dimensional point of view it looks like splotches of color are just popping into and out of existence randomly - much in the way quantum mechanics models particles.

Mr. Roberts apparently has the same issues with quantum mechanics that I do, and he proposes a theory which pretty much offers a simple and intuitive explanation for not only quantum mechanics, but the nature of space time and even the four fundamental forces of physics. While there is really no way to prove or disprove his theory yet, I greatly admire his audacity at thinking outside the box and challenging ideas that are widely accepted even though they don't really make that much sense. His theory is that space is quantum - that spacetime, rather than being an unbroken continuum of empty space, is in fact composed of what he calls "quanta" - discrete, tiny units. When an object moves in space it moves from one quanta to another. This implies that nature is in fact, eleven dimensional - we have the four dimensions we normally experience, plus three additional spatial dimensions and one time dimension in which the quanta exist, and three more dimensions with the quanta.

The genius of Roberts' theory is that it offers a single, unified, intuitive explanation for many physics issues. For example, the four fundamental forces - gravity, nuclear weak, nuclear strong, and electromagnetic - can now be reduced to a single phenomen of vortexes in the quanta. The Planck constants become measurements of the size of the quanta. Time becomes an attribute of the quanta. Why the speed of light is a universal constant is also explained. Quantum tunneling is just particles jumping from one quanta to another through empty spaces in between them, rather than particles vanishing and reappearing somewhere else for no obvious reason.

At it's base, this theory is a variation of Bohmian mechanics or pilot-wave theory, which is a deterministic interpretation of quantum mechanics which uses hidden variables - variables we are not aware of. Adherents of the traditional stochastic Copenhagen interpretation have written proofs that these hidden variables can not exist. While I have not read any of these, the fact that someone can even try to prove that something we don't know about does not exist seems to me to be the height of insanity. Quantum mechanics is often touted as the most successful theory in the history of physics. It is very successful at predicting probabilities, so if you accept that the universe is random that may be true. If however, you believe that things happen for a reason (on a subatomic level) and that those reasons can be understood, the theory becomes a heuristic for predicting what could happen, without really understanding what actually is happening.

Mr. Roberts shares my deep skepticism about received truths. This basically means that nothing you are told or you hear should be accepted as true until you understand the reasoning and/or facts behind it. This book questions the "why" behind much of current physics theory, and realizes that much of it doesn't make sense, so he comes up with another theory that does make sense. While Thad gives no real direct evidence to support his quantum space theory, he does provide a great deal of circumstantial evidence, and he has obviously thought all of it through very carefully (I should note that I am not sure that direct evidence is really possible given our current technology.) However, the fact that he is willing to abandon all of the things that are generally accepted as being true and to think outside the box is just amazing to me. There is nothing I love more than a completely new way of looking at things, and this book definitely provides that

Labels:

books,

science

No comments

This Changes Everything, by Naomi Klein, is a book about climate change, and specifically how having a habitable planet is directly at odds with the fundamental tenets of capitalism.

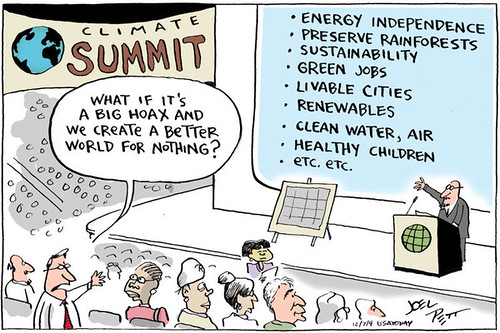

This Changes Everything, by Naomi Klein, is a book about climate change, and specifically how having a habitable planet is directly at odds with the fundamental tenets of capitalism. This cartoon pretty well sums up my thoughts about people who are against environmental reforms. The most common argument these days seems to be that human carbon dioxide emissions are not the cause of climate change, or don't contribute to it in a meaningful way, so we should go ahead and pollute as much as possible. While to me the thought processes that lead to this conclusion are completely insane, one should never underestimate the power of cognitive dissonance. If someone makes money for something, no matter how horrible it is, they will find a way to convince themselves that it is good, or at least tolerable. No one thinks they are evil, the really evil people think everyone else is evil.

This cartoon pretty well sums up my thoughts about people who are against environmental reforms. The most common argument these days seems to be that human carbon dioxide emissions are not the cause of climate change, or don't contribute to it in a meaningful way, so we should go ahead and pollute as much as possible. While to me the thought processes that lead to this conclusion are completely insane, one should never underestimate the power of cognitive dissonance. If someone makes money for something, no matter how horrible it is, they will find a way to convince themselves that it is good, or at least tolerable. No one thinks they are evil, the really evil people think everyone else is evil. I have read and enjoyed a couple other books by Michael Pollan, but was not expecting this one to be as enjoyable as it was. Humans tend to see ourselves as separate from nature, and mostly above nature. This book puts a little spin on that point of view by describing things from the perspective of plants. The book focuses on four plants: apples, tulips, marijuana and potatoes - and describes how those plants have taken advantage of human beings to further their own self-interest.

I have read and enjoyed a couple other books by Michael Pollan, but was not expecting this one to be as enjoyable as it was. Humans tend to see ourselves as separate from nature, and mostly above nature. This book puts a little spin on that point of view by describing things from the perspective of plants. The book focuses on four plants: apples, tulips, marijuana and potatoes - and describes how those plants have taken advantage of human beings to further their own self-interest. Who Stole the American Dream, by Hedrick Smith, is about exactly what you would expect. It explains how and why the wealth in the United States has become so concentrated in the hands of the few. Back in the 1950s and 60s, in what is considered by many to be the height of American prosperity, corporations would act for the benefit of all their stakeholders - their employees, their consumers, society in general. At some point the focus shifted to be on maximizing shareholder value - which means trying to maximize stock price at the expense of everything else.

Who Stole the American Dream, by Hedrick Smith, is about exactly what you would expect. It explains how and why the wealth in the United States has become so concentrated in the hands of the few. Back in the 1950s and 60s, in what is considered by many to be the height of American prosperity, corporations would act for the benefit of all their stakeholders - their employees, their consumers, society in general. At some point the focus shifted to be on maximizing shareholder value - which means trying to maximize stock price at the expense of everything else.  I picked up The Divide: American Injustice in the Age of the Wealth Gap, by Matt Taibbi because I was looking for another book of his, Griftopia, but I couldn't find it in English here in Switzerland. The book was about how income inequality is tied to inequality in the American justice system - specifically how the poor are jailed in huge numbers for ridiculously silly things, while the rich can literally steal billions of dollars and only get a slap on the wrist.

I picked up The Divide: American Injustice in the Age of the Wealth Gap, by Matt Taibbi because I was looking for another book of his, Griftopia, but I couldn't find it in English here in Switzerland. The book was about how income inequality is tied to inequality in the American justice system - specifically how the poor are jailed in huge numbers for ridiculously silly things, while the rich can literally steal billions of dollars and only get a slap on the wrist.